where is mandibular nerve

The mandibular nerve, also known as the inferior alveolar nerve, is a crucial component of the trigeminal nerve, the largest cranial nerve in the human body. It is responsible for providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and lower lip. Understanding the location and function of the mandibular nerve is essential for appreciating its significance in dentistry and diagnosing and treating potential disorders and conditions associated with it.

Understanding the Mandibular Nerve

Definition and Function of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve is the third branch of the trigeminal nerve and emerges from the skull through the mandibular foramen. It plays a vital role in conveying sensory information from the lower jaw and lip to the brain. The primary function of the nerve is to transmit the sensations of touch, pain, and temperature from these areas to ensure normal oral function.

The mandibular nerve is an essential component of the trigeminal nerve, which is the largest cranial nerve in the human body. It is responsible for providing sensory innervation to the face, including the forehead, cheeks, nose, upper and lower lips, and the lower jaw.

When you touch your lower lip or feel the warmth of a hot beverage on your lower jaw, it is the mandibular nerve that carries these sensations to your brain, allowing you to perceive and respond to them accordingly.

Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve

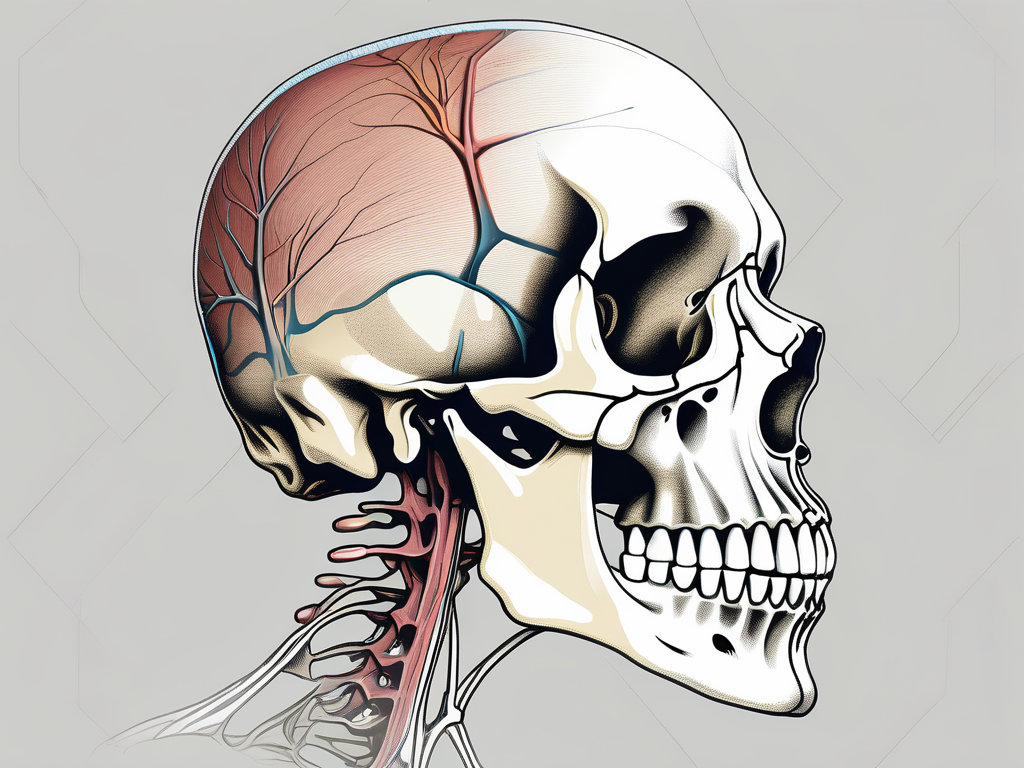

The mandibular nerve originates within the trigeminal ganglion, a sensory ganglion located within the middle cranial fossa. This ganglion is a collection of nerve cell bodies that serves as a relay station for sensory information before it is transmitted to the brain.

From the trigeminal ganglion, the mandibular nerve traverses through the foramen ovale, a small opening in the skull’s base, and descends towards the mandible. As it travels through this bony canal, the nerve is protected and insulated by various layers of connective tissue and bone.

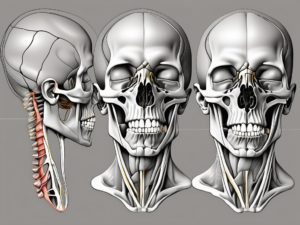

Once in the mandible, the mandibular nerve branches out, giving rise to several smaller nerves that supply different regions of the lower face and oral cavity. These branches include the mental nerve, which innervates the lower lip and chin, and the incisive nerve, which provides sensation to the lower anterior teeth and associated tissues.

The mental nerve emerges from the mental foramen, a small opening located on the anterior surface of the mandible. It courses downward and forward, supplying sensation to the skin of the lower lip and the chin. This nerve is responsible for the ability to feel touch, pain, and temperature in these areas.

The incisive nerve, on the other hand, travels through the mandibular canal, a hollow space within the mandible that houses the roots of the lower anterior teeth. It provides sensory innervation to the lower incisors, canine teeth, and the surrounding tissues. This nerve allows you to perceive sensations such as pressure, temperature, and pain in your lower front teeth.

Understanding the anatomy of the mandibular nerve is crucial in various fields of medicine, particularly dentistry and oral surgery. Dentists rely on their knowledge of the nerve’s distribution to administer local anesthesia effectively and safely, ensuring that patients experience minimal discomfort during dental procedures.

Location of the Mandibular Nerve

Position in the Skull

The mandibular nerve’s course within the skull starts at the trigeminal ganglion, located in the middle cranial fossa near the apex of the petrous temporal bone. This ganglion, also known as the semilunar ganglion, is a sensory ganglion responsible for relaying sensory information from the face to the brain. It is situated within the dura mater, the tough outermost layer of the meninges, which protects the delicate neural structures within the skull.

From the trigeminal ganglion, the mandibular nerve emerges and travels through the foramen ovale, an opening situated in the sphenoid bone’s greater wing. The foramen ovale serves as a passageway for the mandibular nerve to exit the skull and enter the infratemporal fossa, a space located below the temporal bone. This intricate pathway allows the mandibular nerve to innervate various structures in the face, including the lower teeth, gums, and muscles involved in chewing.

As the mandibular nerve traverses through the skull, it is in close proximity to other important structures. The internal carotid artery, a major blood vessel supplying the brain, runs adjacent to the mandibular nerve within the cavernous sinus. This sinus is a cavity located on either side of the sella turcica, a bony depression in the sphenoid bone. The close relationship between the mandibular nerve and the internal carotid artery highlights the importance of careful surgical planning to avoid potential injury to this vital blood vessel.

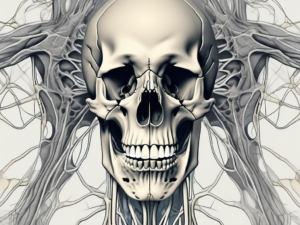

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve shares its course within the skull with other branches of the trigeminal nerve and facial nerve. These include the ophthalmic nerve, responsible for sensory innervation of the forehead, scalp, and upper eyelid, and the maxillary nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the middle part of the face. These intricate relationships can have significant clinical implications, as compression or pathological processes impacting one nerve may potentially affect the function of adjacent nerves.

Relation to Other Facial Nerves

Outside the skull, the mandibular nerve continues its journey, branching into several smaller nerves that innervate different regions of the face. One such branch is the auriculotemporal nerve, which supplies sensory innervation to the skin of the temple and external ear. Another branch, the buccal nerve, provides sensory innervation to the cheek and buccal mucosa.

The mandibular nerve also gives rise to the inferior alveolar nerve, which enters the mandibular foramen on the medial surface of the ramus of the mandible. This nerve provides sensory innervation to the lower teeth, lower lip, and chin. Additionally, it gives off branches that innervate the muscles involved in mastication, such as the masseter and temporalis muscles.

Understanding the intricate anatomy and course of the mandibular nerve is crucial for various medical and dental procedures. Dentists rely on this knowledge to administer local anesthesia effectively and safely during dental procedures involving the lower teeth. Surgeons performing procedures in the infratemporal fossa must be mindful of the mandibular nerve’s location to avoid potential nerve injury and subsequent complications.

Clinical Significance of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, also known as the inferior alveolar nerve, plays a crucial role in the sensory innervation of the lower jaw and teeth. It is one of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve, the largest cranial nerve responsible for facial sensation. The mandibular nerve carries sensory information from the lower lip, chin, lower teeth, gums, and part of the tongue.

Common Disorders and Conditions

The mandibular nerve can be subject to a range of disorders and conditions, affecting its normal function and causing various symptoms. One such example is trigeminal neuralgia, a debilitating condition characterized by severe facial pain. This condition can be triggered by simple activities like talking, eating, or even touching the face. The pain is often described as sharp, shooting, or electric shock-like, and it can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.

Other potential issues that can affect the mandibular nerve include peripheral neuropathies, which are conditions that involve damage to the peripheral nerves. These can result in symptoms such as numbness, tingling, or weakness in the lower jaw and surrounding areas. Infections, such as dental abscesses or herpes zoster (shingles), can also affect the mandibular nerve, leading to localized pain and discomfort.

Tumors, although rare, can also affect the mandibular nerve. These can be benign or malignant growths that put pressure on the nerve, causing pain, numbness, or even facial paralysis. Trauma, such as fractures of the jaw or dental procedures that involve the lower jaw, can also damage the mandibular nerve and result in sensory disturbances.

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJ disorders) can also impact the mandibular nerve. These disorders involve problems with the jaw joint and surrounding muscles, leading to symptoms such as jaw pain, clicking or popping sounds, difficulty chewing, and even referred pain to the ear or head. The mandibular nerve can be affected in TMJ disorders, contributing to the overall discomfort and dysfunction.

Given the wide range of disorders and conditions that can affect the mandibular nerve, it is crucial to consult with a healthcare professional for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment options. A thorough evaluation, including a detailed medical history and physical examination, is essential to identify the underlying cause of the symptoms and develop an effective treatment plan.

Diagnostic Procedures and Treatments

Proper diagnosis of mandibular nerve conditions often requires a comprehensive evaluation, involving various diagnostic procedures. Along with a detailed medical history and physical examination, healthcare professionals may recommend imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans. These imaging techniques can provide detailed images of the mandibular nerve and surrounding structures, helping to identify any abnormalities or sources of compression.

Treatment approaches for mandibular nerve disorders vary depending on the underlying cause and severity of the symptoms. In cases of trigeminal neuralgia, medications such as anticonvulsants or nerve pain medications may be prescribed to manage the pain. Nerve blocks, which involve the injection of an anesthetic near the affected nerve, can also provide temporary relief from the symptoms.

In some cases, physical therapy techniques may be recommended to alleviate symptoms and improve jaw function. These may include exercises to strengthen the jaw muscles, stretches to improve flexibility, and techniques to promote relaxation and reduce muscle tension. In more severe or refractory cases, surgical interventions may be necessary to address the underlying cause of the mandibular nerve disorder. Surgical options can range from decompression procedures to remove any sources of compression on the nerve to more invasive techniques, such as nerve grafts or neurectomy.

Consulting with a medical or dental professional who specializes in or has experience with mandibular nerve disorders is essential to determine the most appropriate course of action. They can assess the individual’s specific condition, consider their medical history and overall health, and tailor a treatment plan that addresses their unique needs and goals.

The Mandibular Nerve in Dentistry

Role in Dental Procedures

Within the field of dentistry, a thorough understanding of the mandibular nerve is imperative to ensure the safe administration of local anesthesia during dental procedures. Accurate identification of the mandibular nerve’s location is crucial to minimize the risk of nerve injury, which could result in adverse effects on oral health and patient comfort.

Dentists employ various techniques to anesthetize the mandibular nerve, such as inferior alveolar nerve blocks and nerve-specific infiltrations. These methods rely on precise knowledge of the mandibular nerve’s course and innervation patterns to achieve successful anesthesia without complications.

During an inferior alveolar nerve block, the dentist carefully locates the mandibular nerve near the mandibular foramen. By injecting an anesthetic agent near the nerve, the dentist can effectively numb the lower teeth, gums, and lip, ensuring a pain-free dental procedure. This technique is commonly used for procedures such as tooth extractions, root canals, and dental implant placements.

In addition to the inferior alveolar nerve block, dentists may also perform nerve-specific infiltrations to target specific branches of the mandibular nerve. By injecting anesthetic near a specific nerve branch, the dentist can achieve localized anesthesia for procedures involving a specific area of the mouth. This technique is commonly used for dental fillings, crown placements, and periodontal treatments.

Implications for Oral Health

The mandibular nerve’s sensory function plays a vital role in maintaining oral health. By providing innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and lip, it enables the perception of potential dental issues such as tooth decay, gum disease, or oral injuries. Regular dental check-ups and prompt dental care are essential to prevent and address problems that may otherwise compromise oral health.

When the mandibular nerve is functioning properly, it allows individuals to detect any abnormalities or discomfort in the lower oral cavity. This early detection is crucial in identifying and treating dental problems before they worsen. For example, if a tooth is experiencing decay, the mandibular nerve will transmit pain signals to the brain, alerting the individual to seek dental treatment.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve’s sensory function extends beyond pain perception. It also enables individuals to sense temperature changes, pressure, and touch in the lower oral region. This sensory feedback is essential for proper chewing and speaking, as it allows individuals to adjust their bite force and tongue movements accordingly.

In cases where the mandibular nerve is compromised or injured, individuals may experience numbness, tingling, or altered sensation in the lower teeth, gums, and lip. This can significantly impact oral health, as it may lead to difficulties in chewing, speaking, and maintaining oral hygiene. Therefore, it is crucial for dentists to have a comprehensive understanding of the mandibular nerve to minimize the risk of nerve injury during dental procedures.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Mandibular Nerve

Can the Mandibular Nerve be Damaged?

While the mandibular nerve is generally well-protected within the skull, it is not impervious to injury. Trauma, dental procedures, infections, or underlying medical conditions can potentially lead to nerve damage. Signs of mandibular nerve damage may include altered sensation, numbness, pain, or difficulty in chewing. If experiencing any unusual symptoms, it is advisable to consult a healthcare professional promptly for evaluation and appropriate management.

The mandibular nerve, also known as the inferior alveolar nerve, is a branch of the trigeminal nerve. It is responsible for providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and lip. This nerve plays a crucial role in oral health and overall well-being.

When it comes to dental procedures, the mandibular nerve can be at risk. Procedures such as wisdom tooth extraction, dental implants, or root canal treatments may pose a potential threat to the nerve. Dentists take great care to minimize the chances of nerve damage during these procedures, but it is still a possibility.

Infections can also affect the mandibular nerve. Conditions like dental abscesses or osteomyelitis, which is an infection of the bone, can cause inflammation and compression of the nerve. This can result in pain, numbness, or altered sensations in the affected area.

Underlying medical conditions, such as trigeminal neuralgia or multiple sclerosis, can also lead to mandibular nerve damage. These conditions affect the nervous system and can cause severe facial pain or sensory disturbances.

What are the Symptoms of Mandibular Nerve Problems?

Mandibular nerve problems can manifest in various ways, including pain, tingling, numbness, or altered sensations in the lower teeth, gums, or lip. In severe cases, individuals may experience difficulty speaking, eating, or performing routine tasks that involve the lower face. Prompt evaluation by a healthcare professional is crucial to determine the underlying cause and develop an effective management plan.

When the mandibular nerve is affected, individuals may experience a sharp or shooting pain in the lower jaw or teeth. This pain can be intermittent or constant, and it may worsen with certain activities like chewing or speaking.

Tingling or a “pins and needles” sensation in the lower lip, gums, or tongue can also be a sign of mandibular nerve problems. This sensation may come and go or persist for longer periods.

In some cases, individuals may experience numbness in the lower face. This can make it difficult to feel hot or cold temperatures, leading to accidental burns or injuries.

Altered sensations, such as a burning or electric shock-like feeling, can also occur. These sensations can be uncomfortable and may affect the individual’s quality of life.

In severe cases, mandibular nerve problems can impact daily activities. Difficulty speaking, eating, or performing routine tasks that involve the lower face can significantly affect a person’s well-being. Seeking medical attention is essential to address these symptoms and prevent further complications.

It is important to note that the symptoms of mandibular nerve problems can vary from person to person. Some individuals may only experience mild discomfort, while others may have more severe symptoms. Consulting a healthcare professional is crucial for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve serves a critical role in providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and lip. Understanding its anatomy, function, and clinical significance is vitally important, particularly within the dental field. While the mandibular nerve can be susceptible to disorders or injuries, seeking professional medical advice and prompt treatment can help ensure optimal oral health and overall well-being.