which foramen does the mandibular nerve pass through

The mandibular nerve is a crucial component of the trigeminal nerve, one of the main cranial nerves responsible for sensory input in the face and motor control of the jaw muscles. Understanding the anatomy and function of the mandibular nerve is essential for healthcare professionals, especially those in the field of dentistry and oral surgery. In this article, we will explore the intricate details of the mandibular nerve, its pathway, and the specific foramen through which it passes.

Understanding the Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve

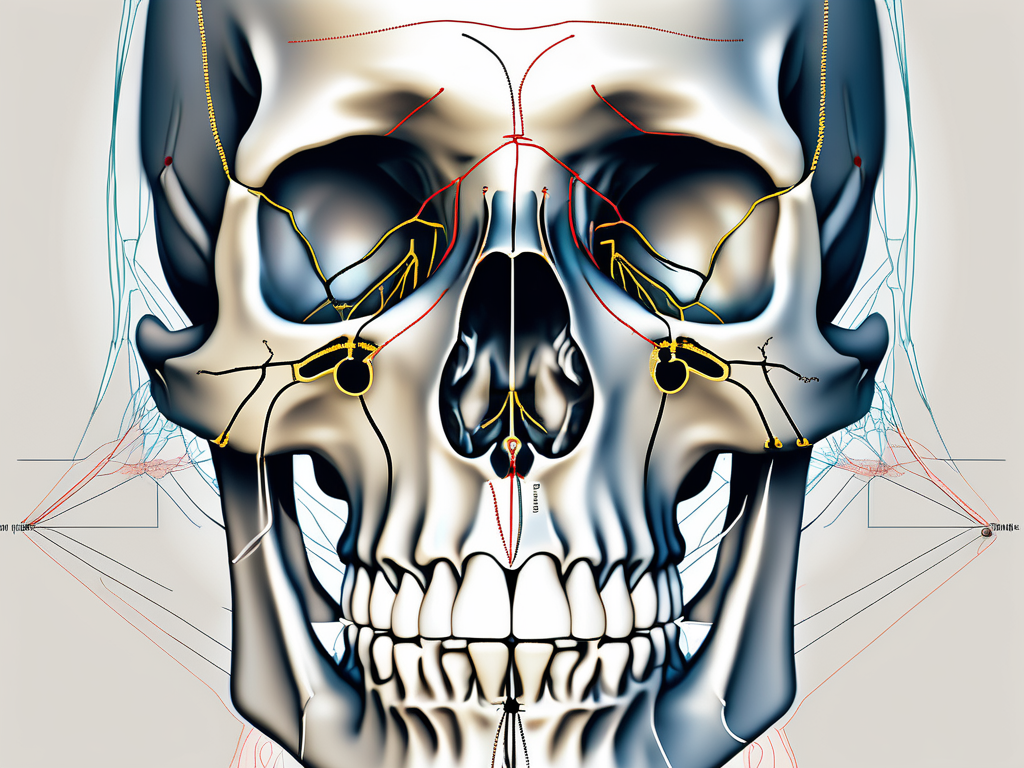

The mandibular nerve is a crucial component of the trigeminal nerve, which is the largest cranial nerve in the human body. It emerges from the trigeminal ganglion, a sensory ganglion located within the middle cranial fossa of the skull. This ganglion contains the cell bodies of the sensory neurons that transmit information from the face and neck to the brain.

The mandibular nerve consists of sensory, motor, and autonomic fibers, each with its own unique role in the functioning of the face and neck. The sensory fibers carry information from the skin, teeth, tongue, and temporomandibular joint. These fibers enable us to perceive sensations such as pain, touch, and temperature, allowing us to interact with the world around us.

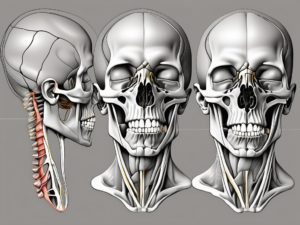

On the other hand, the motor fibers of the mandibular nerve control the movements of the muscles responsible for chewing. These muscles include the masseter, temporalis, lateral pterygoid, and medial pterygoid muscles. When activated, these muscles work in harmony to facilitate the complex process of mastication, allowing us to break down food into smaller, more manageable pieces.

The Origin and Pathway of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve originates from the trigeminal ganglion, which lies in close proximity to the petrous part of the temporal bone. This bone is a dense, pyramid-shaped structure located on the side of the skull. Exiting the skull through the foramen ovale, one of the large openings at the base of the skull, the mandibular nerve enters the infratemporal fossa.

Within the infratemporal fossa, the mandibular nerve takes a complex pathway, traversing several structures before branching out to its respective destinations. One of these structures is the lateral pterygoid muscle, which plays a crucial role in the movement of the jaw. The mandibular nerve also passes through the tensor veli palatini muscle, which is involved in the opening and closing of the auditory tube.

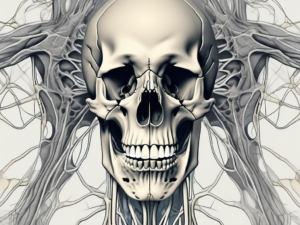

As the mandibular nerve continues its journey, it gives rise to various branches that innervate different regions of the face and neck. These branches include the buccal nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the cheek, and the auriculotemporal nerve, which supplies sensation to the external ear and the temporal region of the scalp.

The Role and Function of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve serves a crucial role in both sensory and motor functions. The sensory fibers of the mandibular nerve provide innervation to the skin of the lower face, the lower lip, the gums, and the lower teeth. Through these sensory fibers, we are able to perceive various sensations, such as pain, touch, and temperature, in these areas.

In addition to sensory fibers, the mandibular nerve also carries autonomic fibers that regulate the blood flow and secretion in salivary glands. These autonomic fibers play a vital role in maintaining the proper functioning of the salivary glands, which are responsible for producing saliva, an essential component of the digestive process.

On the motor side, the mandibular nerve supplies the muscles responsible for mastication, or chewing. The masseter muscle, located in the cheek region, is one of the key muscles involved in the process of chewing. The temporalis muscle, situated on the side of the head, also contributes to the movement of the jaw during chewing. Additionally, the lateral and medial pterygoid muscles, located deep within the jaw, play a crucial role in the coordination and stability of the jaw during mastication.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve is a vital component of the trigeminal nerve, responsible for sensory and motor functions in the face and neck. Its complex origin, pathway, and role in chewing highlight its importance in our daily lives. Understanding the anatomy of the mandibular nerve provides valuable insights into the intricate workings of the human body.

The Foramen: Gateway for Nerves

The word “foramen” refers to an opening or passage in the body through which nerves, blood vessels, or other structures travel. When it comes to the mandibular nerve, a specific foramen serves as its gateway from the skull to the rest of the face and jaw.

The mandibular nerve, also known as the inferior alveolar nerve, is a branch of the trigeminal nerve. It is responsible for providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and lip, as well as motor innervation to the muscles involved in chewing. This nerve plays a crucial role in oral health and function.

Defining the Foramen in Human Anatomy

In human anatomy, a foramen is a natural opening or hole in a bone that allows nerves and blood vessels to pass through. These foramina are crucial for the proper functioning of the body, facilitating the transmission of vital information and resources throughout different regions.

Foramina can be found in various bones of the body, including the skull, spine, and pelvis. They are often named based on their location or the structures that pass through them. The foramen magnum, for example, is the large opening at the base of the skull through which the spinal cord enters and connects to the brainstem.

Foramina vary in size and shape, depending on their specific function and the structures they accommodate. Some foramina are small and narrow, allowing only a single nerve or blood vessel to pass through, while others are larger and can accommodate multiple structures.

Different Types of Foramen and Their Functions

Foramina come in various sizes, shapes, and locations throughout the body. Each serves a specific purpose, enabling the passage of different structures. Some foramina are named after the structures or nerves that traverse them, such as the foramen ovale, through which the mandibular nerve passes. Others possess unique names that originate from anatomical landmarks.

One example of a foramen named after an anatomical landmark is the foramen rotundum, located in the sphenoid bone. It is a round opening that allows the maxillary nerve, another branch of the trigeminal nerve, to pass through. This nerve provides sensory innervation to the upper teeth, gums, and lip.

The foramen lacerum, on the other hand, is a more complex structure located at the base of the skull. It is partially filled with cartilage and serves as a passageway for several important structures, including the internal carotid artery, a major blood vessel that supplies blood to the brain.

Understanding the different types of foramina and their functions is essential in the field of anatomy and medicine. It allows healthcare professionals to accurately diagnose and treat various conditions that may affect the nerves and blood vessels passing through these openings.

The Mandibular Nerve and the Foramen

The foramen ovale, located in the sphenoid bone, is the specific entrance through which the mandibular nerve exits the skull. It is positioned on the lateral aspect of the skull base, posterior to the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The foramen ovale is a key player in the pathway of the mandibular nerve, acting as the bridge between the cranial and facial regions.

The mandibular nerve, also known as the V3 branch of the trigeminal nerve, is responsible for providing sensory and motor innervation to the lower jaw, teeth, gums, and certain muscles involved in chewing. Its journey begins within the skull, where it courses through the foramen ovale, a minuscule opening that accommodates not only the mandibular nerve but also other important structures, including the accessory meningeal artery and the lesser petrosal nerve.

The Specific Foramen for the Mandibular Nerve

The foramen ovale, despite its compact size, accommodates the mandibular nerve alongside other important structures, including the accessory meningeal artery and the lesser petrosal nerve. This minuscule opening provides an intricate channel for the transmission of sensory and motor information, as well as blood supply to the mandibular region.

As the mandibular nerve exits the foramen ovale, it embarks on a fascinating journey through the head and face, playing a crucial role in various sensory and motor functions. This nerve, with its intricate network of branches, ensures the proper functioning of the mandible and its associated structures.

The Journey of the Mandibular Nerve Through the Foramen

After exiting the foramen ovale, the mandibular nerve continues its journey, traversing the infratemporal fossa. This region, situated beneath the temporal bone, houses several essential structures involved in chewing, such as the masseter muscle and the temporomandibular joint.

The mandibular nerve, with its extensive network of branches, provides sensory innervation to various regions of the face. One of its branches, the auriculotemporal nerve, supplies sensation to the skin of the temple and the external ear. This branch plays a crucial role in transmitting sensory information, allowing us to perceive touch, temperature, and pain in these areas.

Another important branch of the mandibular nerve is the buccal nerve. This nerve is responsible for providing sensation to the skin over the cheek. It allows us to feel touch, pressure, and temperature in this region, contributing to our overall sensory experience.

Throughout its course, the mandibular nerve gives rise to multiple branches that innervate different areas. These branches include the mental nerve, which supplies sensation to the lower lip and chin, and the lingual nerve, responsible for providing sensation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

The mandibular nerve, with its intricate pathway and extensive innervation, is a vital component of the craniofacial region. Its role in transmitting sensory and motor information ensures the proper functioning of the mandible and its associated structures, allowing us to perform essential functions such as chewing, speaking, and facial expressions.

Implications of Mandibular Nerve Damage

Injuries or damage to the mandibular nerve can have significant implications on an individual’s oral health and overall quality of life. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and treatment options for mandibular nerve damage is crucial for healthcare professionals to adequately address and assist patients who experience such complications.

Mandibular nerve damage can result from a variety of factors, including traumatic injuries, such as fractures to the skull or facial bones, as well as complications arising from certain medical procedures. Additionally, infections, tumors, or diseases affecting the trigeminal nerve may also lead to mandibular nerve damage.

When it comes to traumatic injuries, motor vehicle accidents, falls, and sports-related incidents are common causes of mandibular nerve damage. The forceful impact on the face or head can result in nerve compression, stretching, or even severing. In some cases, fractures to the skull or facial bones can directly injure the mandibular nerve, leading to long-term complications.

Medical procedures that involve the manipulation or removal of tissues near the mandibular nerve can also pose a risk. For example, during dental procedures like wisdom tooth extraction or dental implant placement, accidental damage to the nerve can occur. Similarly, surgical interventions in the oral and maxillofacial region, such as jaw surgery or tumor removal, carry the potential for mandibular nerve injury.

The symptoms of mandibular nerve damage can vary depending on the extent and location of the injury. Common signs include numbness or altered sensation in the lower face and jaw, difficulty in chewing or speaking, and muscle weakness in the affected area.

Patients with mandibular nerve damage may experience a tingling or “pins and needles” sensation in the lower face and jaw. This altered sensation can range from mild to severe, and it may affect one side or both sides of the face. Some individuals may also report a loss of sensation, where they are unable to feel touch, temperature, or pain in the affected area.

In addition to sensory changes, mandibular nerve damage can lead to functional impairments. Chewing and speaking may become challenging due to muscle weakness or coordination problems. Patients may struggle to bite down or experience difficulty in moving their jaw properly. These difficulties can significantly impact a person’s ability to eat, speak clearly, and maintain oral hygiene.

Treatment approaches for mandibular nerve damage depend on the underlying cause and severity of the condition. Healthcare professionals may consider a combination of medication, physical therapy, and surgical interventions to address functional impairments and alleviate pain. Individual cases may require tailored approaches, and it is essential for patients to consult with their healthcare providers for appropriate guidance and treatment.

Medication can be prescribed to manage pain and reduce inflammation associated with mandibular nerve damage. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and nerve pain medications, such as gabapentin or amitriptyline, may be used to provide relief. In some cases, corticosteroids may be administered to reduce nerve inflammation and promote healing.

Physical therapy plays a crucial role in the rehabilitation of mandibular nerve damage. Therapeutic exercises can help improve muscle strength, coordination, and range of motion. Physical therapists may also employ techniques like electrical stimulation or ultrasound therapy to aid in nerve regeneration and reduce pain.

In severe cases where conservative treatments are ineffective, surgical interventions may be necessary. Nerve repair or grafting procedures can be performed to reconnect or replace damaged segments of the mandibular nerve. These surgical techniques aim to restore nerve function and improve the patient’s overall quality of life.

It is important to note that the recovery process for mandibular nerve damage can vary from person to person. Some individuals may experience partial or complete recovery, while others may have long-term or permanent complications. Regular follow-up appointments with healthcare professionals are crucial to monitor progress, address any concerns, and adjust treatment plans accordingly.

The Connection Between the Mandibular Nerve and Dental Health

The mandibular nerve plays a pivotal role in dental health, especially when it comes to dental procedures and oral surgery. Dentists and oral surgeons must have a comprehensive understanding of the mandibular nerve’s proximity and vulnerability to ensure optimal oral care.

The Mandibular Nerve in Dental Procedures

Dental procedures, such as extractions, root canals, and implant surgeries, require careful consideration of the mandibular nerve. Dentists must take precautions to avoid direct contact or damage to the nerve during these interventions. This may involve utilizing special imaging techniques, such as cone beam computed tomography, to accurately assess the nerve’s location in relation to the treatment site.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve supplies sensory information to the lower teeth, gums, and lower lip. It also provides motor innervation to the muscles responsible for chewing, such as the masseter and temporalis muscles. Understanding the intricate relationship between the mandibular nerve and dental procedures allows dentists to provide effective and safe treatment options for their patients.

Protecting the Mandibular Nerve During Oral Surgery

During more complex oral surgeries, such as orthognathic surgery or temporomandibular joint replacements, protecting the integrity of the mandibular nerve becomes even more critical. Surgeons with expertise in maxillofacial surgery take into account the nerve’s position and carefully work around it to minimize the risk of damage.

Moreover, the mandibular nerve is part of the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions such as biting and chewing. It is the largest of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve and has multiple divisions that innervate different areas of the face and mouth. This intricate network of nerves requires meticulous surgical techniques to ensure the preservation of its function and prevent any post-operative complications.

Additionally, advancements in surgical technology, such as intraoperative nerve monitoring, have further improved the safety and precision of surgical procedures involving the mandibular nerve. This technique allows surgeons to monitor the nerve’s function in real-time, providing immediate feedback and enabling them to make adjustments if necessary.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve, a crucial component of the trigeminal nerve, passes through the foramen ovale, one of the key openings in the base of the skull. Understanding the anatomy, pathway, and function of the mandibular nerve is essential for healthcare professionals in providing comprehensive care for individuals with dental needs. While injuries or damage to the mandibular nerve can have significant implications, proper evaluation, treatment, and surgical techniques can help protect and preserve this vital nerve, ensuring optimal oral health and overall well-being.