what does the mandibular nerve loop around

The mandibular nerve is a critical component of the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for delivering sensory information from the face to the brain. It is the largest of the three divisions of the trigeminal nerve and holds significant clinical importance. Understanding the anatomy and function of the mandibular nerve is crucial in comprehending its course and the structures it interacts with. Furthermore, recognizing the clinical significance of the mandibular nerve loop can aid in anticipating potential complications in dental and surgical procedures.

Understanding the Mandibular Nerve

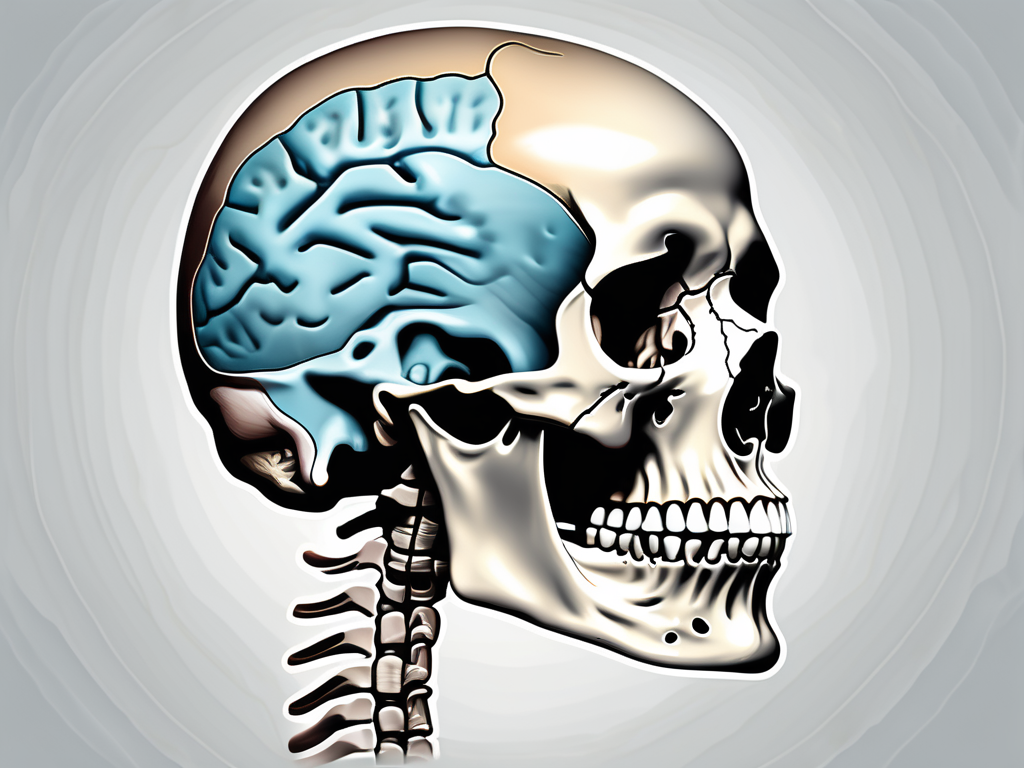

The mandibular nerve is a crucial component of the trigeminal nerve, which is responsible for providing sensory and motor innervation to the face. It emerges from the trigeminal ganglion located in the middle cranial fossa, a depression in the floor of the skull. This ganglion is a collection of cell bodies of sensory neurons that transmit information from the face to the brain.

Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve originates from the posterior part of the trigeminal ganglion, and its fibers combine to form a distinct triangular-shaped trunk called the main (or primary) trunk. This main trunk then splits into two major branches: the anterior division and the posterior division.

The anterior division of the mandibular nerve supplies sensory fibers to regions such as the skin of the chin, lower lip, lower teeth, and part of the tongue. These sensory fibers play a crucial role in our ability to perceive touch, temperature, and pain in these areas. They provide us with the ability to feel sensations such as a gentle touch, a hot beverage, or a painful toothache.

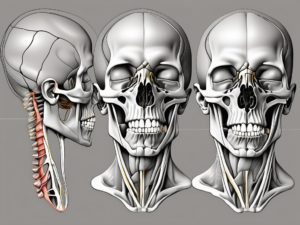

On the other hand, the posterior division of the mandibular nerve innervates the muscles involved in chewing or mastication. These muscles include the temporalis, masseter, and lateral and medial pterygoid muscles. The motor fibers originating from the posterior division control the contraction and relaxation of these muscles, allowing for the complex movements required for biting, chewing, and jaw movement.

Functions of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve serves both sensory and motor functions, making it a vital component of the trigeminal nerve. The sensory fibers provide tactile, thermal, and nociceptive sensations to the skin, mucosa, and teeth of the lower face. These fibers transmit valuable information to the brain, enabling us to perceive a range of tactile stimuli and respond appropriately. Whether it’s feeling the warmth of a cup of coffee or sensing the pain of a dental cavity, the sensory fibers of the mandibular nerve play a crucial role in our daily lives.

Motor fibers originating from the posterior division of the mandibular nerve control the muscles involved in biting, chewing, and jaw movement. The temporalis muscle, located on the side of the head, helps with the closing of the jaw. The masseter muscle, which is the primary muscle responsible for chewing, aids in the grinding and crushing of food. The lateral and medial pterygoid muscles, located deep within the jaw, assist in the side-to-side movement of the jaw during chewing. This intricate motor supply allows for the efficient processing of food during mastication, aiding in digestion and overall oral health.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve is a vital component of the trigeminal nerve, providing both sensory and motor innervation to the lower face. Its sensory fibers enable us to perceive touch, temperature, and pain, while its motor fibers control the muscles involved in biting, chewing, and jaw movement. Understanding the anatomy and functions of the mandibular nerve is essential for comprehending the complex processes involved in facial sensation and mastication.

The Pathway of the Mandibular Nerve

Origin and Course of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, also known as the V3 branch of the trigeminal nerve, is a crucial component of the sensory and motor innervation of the face. It originates from the trigeminal ganglion, a sensory ganglion located within the skull. From there, it quickly exits through the foramen ovale, an opening located in the greater wing of the sphenoid bone.

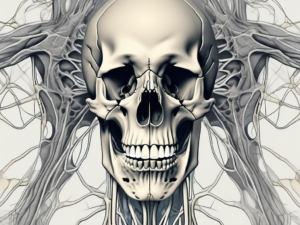

Once it emerges from the foramen ovale, the mandibular nerve embarks on its intricate journey through the head and face. It descends downwards, passing through the infratemporal fossa, a space located below the temporal bone. Along its course, the mandibular nerve interacts with other vital structures such as the maxillary artery and pterygoid muscles, forming a complex network of anatomical relationships.

As the mandibular nerve travels through the head and face, it navigates through a series of bony canals and foramina, ensuring its safe passage and preservation. These bony structures act as protective conduits for the nerve, minimizing the risk of injury. The intricate design of these canals and foramina reflects the remarkable evolutionary adaptation of the human skull to safeguard the delicate neural structures within.

Key Landmarks in the Mandibular Nerve Pathway

Several landmarks hold particular significance along the pathway of the mandibular nerve, providing valuable anatomical reference points for clinicians and researchers alike.

One such landmark is the trigeminal ganglion, where the mandibular nerve originates. This sensory ganglion serves as a crucial relay station for the transmission of sensory information from the face to the brain. It is a site of convergence for various sensory fibers, allowing for the integration and processing of sensory stimuli before relaying them to higher centers in the central nervous system.

Another essential landmark along the pathway of the mandibular nerve is the foramen ovale. This anatomical structure serves as the exit point for the nerve as it leaves the skull. The identification and understanding of this opening are particularly relevant during surgical procedures that involve access to the mandibular nerve. Surgeons must navigate this intricate pathway with precision and care to avoid any damage to the nerve or surrounding structures.

Lastly, it is important to note the locations of the various bony canals and foramina that the mandibular nerve traverses. One such canal is the mandibular canal, which runs through the body of the mandible, the lower jawbone. This canal houses the inferior alveolar nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve responsible for providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth and gums. Another significant foramen is the mental foramen, located on the anterior aspect of the mandible. This foramen allows for the passage of the mental nerve, a terminal branch of the inferior alveolar nerve that supplies sensation to the chin and lower lip.

Understanding the locations and functions of these bony canals and foramina is crucial for dental professionals, oral surgeons, and anatomists. It enables them to accurately diagnose and treat various conditions affecting the mandibular nerve and its branches, ensuring optimal functioning and preventing any potential compression or injury.

What the Mandibular Nerve Loops Around

The Mandibular Nerve and the Middle Ear

The mandibular nerve, the largest branch of the trigeminal nerve, has an intriguing relationship with the middle ear, another intricately structured region of the head. Although they do not directly connect or interact, the mandibular nerve’s path runs parallel to the middle ear structures, separated only by a thin layer of bone.

This close proximity between the mandibular nerve and the middle ear has significant clinical implications. Knowledge of this anatomical relationship is essential for physicians and surgeons, as potential complications may arise during procedures involving both the mandibular nerve and the middle ear. Extreme caution must be exercised to avoid damage to either structure.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve’s proximity to the middle ear can also have implications for patients experiencing certain medical conditions. For example, individuals with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders may experience referred pain in the middle ear due to the shared sensory pathways between the mandibular nerve and the ear. Understanding this connection can aid in the accurate diagnosis and management of such conditions.

The Mandibular Nerve and the Lower Jaw

The mandibular nerve plays a central role in the sensory innervation of the lower jaw, making it an integral component of oral health. The nerve supplies vital sensory information to the lower teeth, allowing for appropriate responses to various external stimuli.

Moreover, the mandibular nerve interacts with the muscles of mastication, specifically the masseter and pterygoid muscles. These muscles are responsible for jaw movement, facilitating biting and chewing. The close relationship between the mandibular nerve and the lower jaw highlights their interdependence in maintaining optimal oral function.

In addition to its sensory and motor functions, the mandibular nerve also carries autonomic fibers that contribute to the regulation of blood flow and saliva production in the lower jaw. This intricate network of nerve fibers ensures the proper functioning of the oral cavity and aids in maintaining oral health.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve’s association with the lower jaw extends beyond its role in oral health. In certain dental procedures, such as dental implant placement or orthognathic surgery, the mandibular nerve’s position and course must be carefully considered to avoid nerve injury and subsequent sensory deficits. Dentists and oral surgeons meticulously plan these procedures, taking into account the intricate relationship between the mandibular nerve and the lower jaw.

Overall, the mandibular nerve’s involvement with the middle ear and the lower jaw highlights its significance in the intricate anatomy and function of the head and neck region. Its close proximity to these structures necessitates careful consideration and expertise when dealing with procedures or conditions involving the mandibular nerve. Understanding the complex interplay between the mandibular nerve, the middle ear, and the lower jaw is crucial for healthcare professionals in providing optimal care for their patients.

Clinical Significance of the Mandibular Nerve Loop

Implications for Dental Procedures

For dentists and oral surgeons, a comprehensive understanding of the mandibular nerve loop is crucial during various dental procedures. When performing procedures such as dental extractions or implant placements, proximity to the mandibular nerve poses potential risks.

It is vital for dental professionals to assess the position of the mandibular nerve relative to the planned procedure, ensuring a safe and successful outcome. This assessment may involve advanced imaging techniques, such as cone beam computed tomography, to accurately visualize the nerve’s course and avoid inadvertent damage.

Moreover, the mandibular nerve loop’s complex anatomy requires dentists to exercise caution and precision. The nerve loop, which originates from the trigeminal ganglion, courses through the infratemporal fossa and enters the mandibular foramen. From there, it divides into its terminal branches, providing sensory innervation to the lower teeth, gums, and chin.

Patients with concerns regarding dental procedures should consult with their dentists, who possess the necessary expertise to provide personalized advice and address individual patient needs. Dentists can discuss the potential risks associated with the mandibular nerve loop and develop appropriate treatment plans to ensure patient safety.

Impact on Surgical Procedures

Beyond dental procedures, the mandibular nerve loop’s knowledge is equally critical during surgical interventions involving the head and neck region. Surgeons performing procedures in this area should be aware of the mandibular nerve’s course and its relationship with neighboring structures.

Surgical specialties, such as maxillofacial surgery or otolaryngology, routinely encounter situations where knowledge of the mandibular nerve loop is indispensable. By adhering to meticulous surgical techniques and maintaining a thorough understanding of the nerve’s anatomical pathway, surgical complications can be minimized.

During surgical interventions, the mandibular nerve loop’s close association with the pterygoid muscles, temporomandibular joint, and other vital structures necessitates careful dissection and preservation. Surgeons must navigate this intricate network of nerves and tissues to achieve optimal surgical outcomes.

Individuals seeking surgical interventions that involve the mandibular nerve should consult with qualified surgeons, who possess the expertise necessary to assess and manage surgical risks effectively. These surgeons can provide detailed explanations of the surgical procedure, including the potential impact on the mandibular nerve loop, and address any concerns or questions the patient may have.

Disorders Related to the Mandibular Nerve

Trigeminal Neuralgia and the Mandibular Nerve

Trigeminal neuralgia is a chronic pain condition affecting the trigeminal nerve and is often associated with the mandibular nerve division. It is characterized by severe, episodic facial pain that can be triggered by mundane activities such as eating or speaking.

The precise etiology of trigeminal neuralgia remains unclear, but it is thought to arise from the compression or irritation of the trigeminal nerve, commonly at the location where the mandibular nerve exits the skull. This condition can result in excruciating pain, significantly impacting an individual’s quality of life.

Living with trigeminal neuralgia can be challenging, as the pain can be debilitating and unpredictable. Simple tasks like eating or talking can become sources of immense discomfort. It is important for individuals experiencing these symptoms to seek medical attention promptly to receive an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Healthcare professionals experienced in managing such conditions can provide valuable guidance and support throughout the journey of managing trigeminal neuralgia.

When it comes to treatment options, there are several approaches that healthcare professionals may consider. Medications, such as anticonvulsants or muscle relaxants, can help manage the pain associated with trigeminal neuralgia. In some cases, surgical interventions may be necessary to relieve pressure on the affected nerve. These procedures can range from microvascular decompression, which involves repositioning blood vessels that may be compressing the nerve, to radiofrequency ablation, which uses heat to disrupt the pain signals.

Mandibular Nerve Damage and its Effects

Damage to the mandibular nerve can occur due to various factors, including trauma, surgical complications, or underlying medical conditions. The consequences of such damage can range from sensory disturbances, such as numbness or tingling, to motor deficits, resulting in impaired jaw movement and difficulty in chewing.

When the mandibular nerve is damaged, it can have a profound impact on an individual’s daily life. Simple tasks like biting into an apple or speaking clearly can become challenging and frustrating. The loss of sensation in the lower face can also affect one’s ability to detect temperature and pain, making it important to take extra precautions to prevent accidental injuries.

Recovery from mandibular nerve damage can vary depending on the extent and severity of the injury. In some cases, the nerve may regenerate naturally over time, leading to gradual improvement of symptoms. However, in more severe cases, surgical interventions or other specialized treatments may be necessary to restore function and alleviate discomfort.

It is crucial for individuals experiencing persistent numbness, weakness, or any other abnormal sensations in the lower face to seek medical attention from healthcare providers familiar with nerve injuries. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management strategies can help alleviate symptoms and facilitate the recovery process. Physical therapy and rehabilitation techniques may also be recommended to improve jaw movement and regain functionality.

Living with mandibular nerve damage can be challenging, but with the right support and treatment, individuals can regain control over their lives and improve their overall well-being. It is important to work closely with healthcare professionals to develop a personalized treatment plan that addresses individual needs and goals.

Treatment and Management of Mandibular Nerve Disorders

Non-Surgical Treatment Options

Non-surgical treatment options are typically the first line of intervention for many mandibular nerve disorders. These may include pharmacological approaches such as pain medications, anticonvulsants, or nerve blocks to alleviate symptoms and improve quality of life.

In addition to medications, complementary therapies such as physical therapy or acupuncture can also provide relief and aid in the recovery process. These non-invasive approaches are often employed as adjuncts to conventional treatments and may have positive effects when used in combination.

It is important to note that the most appropriate treatment path varies depending on the underlying condition and individual patient characteristics. Therefore, individuals with mandibular nerve disorders should consult with healthcare professionals experienced in managing such conditions to receive personalized treatment plans.

Surgical Interventions for Mandibular Nerve Disorders

In cases where non-surgical approaches yield insufficient results or fail to address the underlying cause, surgical intervention may be considered. Surgical options include decompression procedures, where the nerve is freed from any entrapment or compression, or neuromodulation techniques that aim to alter nerve function and alleviate symptoms.

Surgical interventions for mandibular nerve disorders are complex procedures that require specialized expertise. Patients considering surgical options should seek consultations with experienced surgeons, who can thoroughly assess the risks and benefits and provide individualized recommendations based on their specific needs and circumstances.

In conclusion, comprehending the intricate pathway of the mandibular nerve and its interactions with neighboring structures is crucial to understand its clinical significance. Awareness of the mandibular nerve’s relationship with the middle ear and lower jaw is fundamental to avoid potential complications during dental and surgical procedures. Moreover, recognizing and managing mandibular nerve disorders, such as trigeminal neuralgia or nerve damage, necessitates consultation with healthcare professionals well-versed in the diagnosis and treatment of these conditions. By combining knowledge, expertise, and individualized care, clinicians can best address the needs of patients and ensure the optimal management of mandibular nerve-related concerns.