mandibular nerve runs through what

The mandibular nerve, also known as the V3 branch of the trigeminal nerve, is an essential component of the trigeminal nerve complex. As one of the major divisions of the trigeminal nerve, the mandibular nerve plays a crucial role in innervating various structures of the face, including the lower jaw, teeth, gums, and tongue. Understanding the anatomy, functions, and clinical significance of the mandibular nerve is fundamental for dental and medical professionals alike. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the mandibular nerve, its pathway, clinical implications, and frequently asked questions.

Understanding the Mandibular Nerve

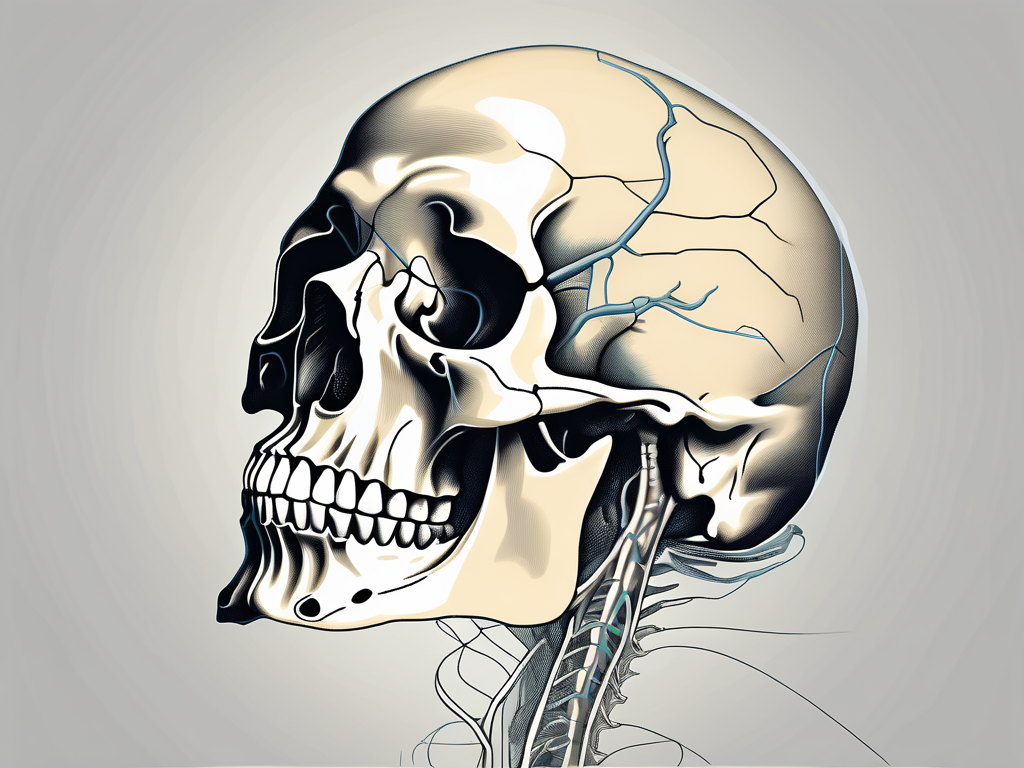

Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, also known as the V3 branch of the trigeminal nerve, is an essential component of the cranial nervous system. It emerges from the trigeminal ganglion, a sensory ganglion located in the middle cranial fossa. This ganglion serves as a relay station for sensory information from the face, head, and oral cavity.

As the largest of the three primary branches of the trigeminal nerve, the mandibular nerve extends inferiorly towards the mandible, or lower jaw. Its course takes it through the infratemporal fossa, a region located deep within the skull. Within this fossa, the mandibular nerve gives rise to several branches, each with its own unique function.

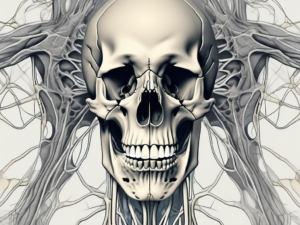

One of these branches is the auriculotemporal nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the temporal region of the head. This allows us to perceive sensations such as touch, temperature, and pain in this area. Another branch, the inferior alveolar nerve, supplies sensory fibers to the mandibular teeth and gingiva, ensuring our ability to perceive oral sensations accurately.

Additionally, the mandibular nerve gives off the lingual nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. This allows us to taste and perceive sensations on the surface of the tongue, contributing to our ability to enjoy and differentiate flavors.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve plays a role in motor function as well. It gives off motor branches such as the masseteric nerve, which innervates the masseter muscle responsible for mastication, or chewing. This muscle allows us to break down food into smaller, more manageable pieces, facilitating the process of digestion.

Functions of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve carries both sensory and motor fibers, making it crucial for various functions related to the oral cavity and jaw movements. The sensory fibers transmit information about touch, temperature, pain, and proprioception from the mandible, lower teeth, gingiva, and tongue to the brain.

Thanks to the sensory information provided by the mandibular nerve, we are able to perceive oral sensations accurately. This allows us to chew our food effectively, ensuring that it is adequately broken down for digestion. It also enables us to speak clearly and swallow comfortably, as we can detect any abnormalities or discomfort in the oral cavity.

In addition to its sensory function, the mandibular nerve also plays a crucial role in motor function. The motor fibers of the mandibular nerve innervate the muscles responsible for jaw movements. These muscles, including the masseter, temporalis, and medial pterygoid, allow us to open and close our mouths with ease, facilitating actions such as speaking, chewing, and yawning.

Overall, the mandibular nerve is a complex and vital component of the cranial nervous system. Its intricate anatomy and multifaceted functions contribute to our ability to perceive and interact with the world around us, particularly in relation to the oral cavity and jaw movements.

The Pathway of the Mandibular Nerve

Origin and Termination Points

The mandibular nerve, also known as the V3 branch of the trigeminal nerve, begins its journey at the trigeminal ganglion, which is positioned within the middle cranial fossa near the base of the skull. This ganglion is a sensory ganglion that contains the cell bodies of the sensory neurons that transmit information from the face to the brain.

Emerging from the trigeminal ganglion, the mandibular nerve traverses through the foramen ovale, a bony aperture in the skull located in the middle cranial fossa. This foramen provides a passage for the nerve to exit the skull and continue its course.

From the foramen ovale, the mandibular nerve courses along the infratemporal fossa, a space between the temporal and maxillary bones. Within this region, the nerve gives rise to several branches, each serving a distinct sensory or motor function.

Finally, the mandibular nerve terminates by dividing into smaller branches that supply innervation to specific areas, including the temporomandibular joint, facial skin, and salivary glands. These branches ensure the proper functioning of the muscles and sensory perception in the lower face.

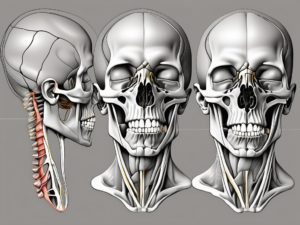

Structures Encountered Along the Pathway

As the mandibular nerve travels through the infratemporal fossa, it encounters various anatomical structures with clinical relevance. Notably, the nerve interacts with the medial and lateral pterygoid muscles, two important muscles involved in mandibular movement. These muscles play a crucial role in chewing and jaw opening, allowing for proper mastication and speech production.

Additionally, the mandibular nerve runs in close proximity to the maxillary artery and its branches, which supply vital structures within the oral cavity. This close association highlights the significance of mindful surgical techniques to prevent inadvertent damage to both the nerve and vascular structures. Surgeons must exercise caution and precision to preserve the integrity of these important anatomical components during procedures such as dental extractions, maxillofacial surgeries, and nerve blocks.

Moreover, the mandibular nerve also passes near the otic ganglion, a small parasympathetic ganglion located just below the foramen ovale. This ganglion provides parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland, which is responsible for producing saliva. The close proximity of the mandibular nerve to the otic ganglion underscores the intricate connections between the nervous and salivary systems.

Furthermore, the mandibular nerve communicates with other branches of the trigeminal nerve, such as the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions. These connections allow for coordinated sensory and motor functions throughout the face, ensuring proper facial expressions, sensation, and reflexes.

In summary, the pathway of the mandibular nerve is a complex and intricate journey that involves various anatomical structures and functions. Understanding the detailed anatomy and relationships along this pathway is crucial for healthcare professionals, particularly those involved in oral and maxillofacial surgery, dentistry, and neurology.

Clinical Significance of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve plays a crucial role in the sensory and motor functions of the face and jaw. It is one of the three branches of the trigeminal nerve, the largest cranial nerve responsible for providing sensation to the face and controlling the muscles involved in chewing.

Conditions that affect the mandibular nerve can lead to a wide range of sensory and motor disturbances. One such condition is trigeminal neuralgia, a debilitating facial pain disorder. Individuals with trigeminal neuralgia experience sudden, severe, and recurrent episodes of facial pain, often triggered by simple activities such as eating or speaking.

In addition to trigeminal neuralgia, there are several other conditions that may impact the mandibular nerve. Temporomandibular joint disorders, which affect the joint connecting the jawbone to the skull, can cause pain, stiffness, and difficulty in jaw movement. Oral infections, such as abscesses or gum disease, can also lead to inflammation and compression of the mandibular nerve, resulting in pain and numbness in the affected area.

Another common issue related to the mandibular nerve is the presence of impacted wisdom teeth. When wisdom teeth do not fully emerge or grow in an abnormal position, they can exert pressure on the surrounding tissues, including the mandibular nerve. This pressure can cause pain, swelling, and even difficulty in opening the mouth.

Furthermore, trauma to the face or jaw, such as fractures or dislocations, can directly damage the mandibular nerve. In these cases, individuals may experience a loss of sensation or motor function in the affected area, requiring immediate medical attention.

Diagnostic Procedures and Treatments

When diagnosing conditions related to the mandibular nerve, healthcare professionals employ various diagnostic procedures to accurately evaluate the underlying cause. A comprehensive medical history assessment is often the first step, as it helps identify any potential risk factors or previous injuries that may contribute to the symptoms.

Following the medical history assessment, a detailed physical examination is conducted to assess the range of motion in the jaw, identify any areas of tenderness or swelling, and evaluate the overall function of the mandibular nerve. In some cases, additional diagnostic tests may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Advanced imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, are commonly used to provide detailed images of the mandibular nerve and surrounding structures. These imaging tests can help identify any abnormalities, such as nerve compression or structural damage, that may be causing the symptoms.

Treatment approaches for mandibular nerve-related conditions depend on the specific diagnosis and the severity of symptoms. In less severe cases, conservative measures such as pain management techniques, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications may be recommended. These can include the use of over-the-counter pain relievers, application of heat or cold packs, and avoiding activities that aggravate the symptoms.

In more severe cases, surgical interventions may be necessary. Nerve blocks, which involve injecting medication near the affected nerve to temporarily numb it, can provide relief from pain and allow for further evaluation of the underlying cause. In certain situations, decompression surgeries may be performed to relieve pressure on the mandibular nerve and restore its normal function.

It is important for individuals experiencing persistent or worsening symptoms related to the mandibular nerve to seek professional medical evaluation. Only a qualified healthcare professional can provide an accurate diagnosis and recommend the most appropriate course of treatment for each individual case.

The Mandibular Nerve in Dental Procedures

Role in Anesthesia Administration

The mandibular nerve plays a pivotal role in dental anesthesia administration, particularly in procedures involving the lower teeth and surrounding structures. By targeting specific nerves connected to the mandibular nerve, dental professionals can successfully achieve anesthesia in the lower jaw, reducing discomfort during dental treatments.

When administering anesthesia in the lower jaw, dental professionals often rely on various techniques to ensure effective numbing of the targeted area. One commonly used technique is the inferior alveolar nerve block. This involves the precise deposition of anesthetic agents around the nerves associated with the mandibular nerve, effectively numbing the lower teeth and surrounding tissues.

In addition to the inferior alveolar nerve block, dental professionals may also utilize mental nerve blocks and incisive nerve blocks. These techniques involve the careful administration of anesthetic agents to specific nerves connected to the mandibular nerve, further enhancing the anesthesia’s effectiveness.

By employing these anesthesia administration techniques, dental professionals can ensure that patients experience minimal discomfort during dental procedures involving the lower jaw. This not only enhances patient comfort but also allows for more efficient and effective dental treatments.

Implications in Oral Surgery

Oral surgery procedures, such as impacted wisdom teeth extractions or dental implant placements, often require meticulous management of the mandibular nerve to prevent injury and promote optimal patient outcomes.

During oral surgery, dentists and oral surgeons undergo extensive training to carefully navigate the anatomical structures associated with the mandibular nerve. This includes a thorough understanding of the nerve’s location, branches, and surrounding tissues. By having this knowledge, dental professionals can perform surgical procedures with precision, minimizing the risk of nerve damage.

Preserving the function of the mandibular nerve is crucial in oral surgery as it ensures the patient’s ability to chew, speak, and feel sensations in the lower jaw remains intact. Dentists and oral surgeons take great care to avoid any unnecessary trauma to the nerve, utilizing specialized instruments and techniques to minimize the risk of nerve injury.

By prioritizing the preservation of the mandibular nerve, dental professionals can provide patients with optimal outcomes following oral surgery procedures. This includes a faster recovery time, reduced post-operative pain, and a decreased likelihood of long-term complications.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve plays a vital role in dental procedures, particularly in anesthesia administration and oral surgery. By understanding the intricate anatomy and employing precise techniques, dental professionals can ensure patient comfort and promote successful outcomes in dental treatments involving the lower jaw.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Mandibular Nerve

Common Misconceptions

There are several common misconceptions surrounding the mandibular nerve that warrant clarification. One common misconception is the belief that the mandibular nerve solely contributes to pain perception in the lower jaw. In reality, the mandibular nerve serves a broader range of functions, including motor control and sensory innervation in multiple structures of the face and oral cavity.

For instance, the mandibular nerve plays a crucial role in the movement of the muscles responsible for chewing, known as the masticatory muscles. These muscles, including the temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid, receive motor innervation from branches of the mandibular nerve. This allows for the coordinated and precise movements required for effective chewing and biting.

In addition to motor control, the mandibular nerve also provides sensory innervation to various regions of the face and oral cavity. This includes the lower teeth and gums, the lower lip, the chin, and parts of the tongue. The sensory information transmitted by the mandibular nerve allows for the perception of touch, temperature, and pain in these areas.

Therefore, it is essential to dispel such misconceptions to ensure a better understanding of the mandibular nerve’s significance in oral health and overall well-being.

Expert Answers to Queries

Q: Can a damaged mandibular nerve regenerate?

A: The regenerative capacity of the mandibular nerve depends on various factors, including the extent and nature of the damage. While minor injuries may heal spontaneously over time, significant trauma or severance of the nerve may require surgical intervention or other forms of specialized treatment. It is important to note that nerve regeneration is a complex process and may not always result in complete restoration of function. Consulting with a healthcare professional with expertise in nerve injuries is crucial for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate management of individual cases.

Q: Can oral infections affect the mandibular nerve?

A: Yes, oral infections such as periodontal abscesses or dental caries can potentially lead to inflammation and localized swelling in the vicinity of the mandibular nerve. This inflammation can exert pressure on the nerve fibers, causing pain or other sensory disturbances. It is important to seek prompt dental evaluation and treatment to address the underlying infection and prevent potential complications. Proper oral hygiene practices, including regular brushing, flossing, and dental check-ups, can help reduce the risk of oral infections and their potential impact on the mandibular nerve.

Q: How can I prevent damage to the mandibular nerve during dental procedures?

A: Preventing damage to the mandibular nerve during dental procedures primarily involves careful technique and strict adherence to anatomical landmarks. Dentists and oral surgeons are extensively trained to maintain a comprehensive understanding of the anatomy and take necessary precautions to protect the mandibular nerve. Before any dental procedure, your dental care provider will thoroughly assess your oral anatomy, including the position of the mandibular nerve, to ensure safe and effective treatment. Patients should communicate any concerns or questions to their dental care providers to ensure optimal safety during dental treatments.

It is important to note that while every effort is made to minimize the risk of nerve damage during dental procedures, complications can still occur in rare cases. If you experience any unusual symptoms, such as persistent numbness, tingling, or pain following a dental procedure, it is important to contact your dental care provider for further evaluation and management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve is a vital component of the trigeminal nerve complex, serving diverse functions associated with sensory and motor innervation of various structures in the face and oral cavity. Understanding the anatomy, functions, and clinical significance of the mandibular nerve is essential in the fields of dentistry and medicine.

While this article provides a comprehensive overview, it is crucial to seek professional medical advice for concerns related to the mandibular nerve. Healthcare professionals with expertise in orofacial anatomy and neurology can evaluate and manage individual cases based on their specific needs, ensuring the highest quality of care.