where does the mandibular nerve exit/enter

The mandibular nerve, one of the branches of the trigeminal nerve, is a crucial component of the sensory innervation of the face. It is responsible for transmitting sensory information from the lower jaw, the lower lip, and the skin and mucous membranes of the lower face. Understanding the anatomy, function, and clinical significance of the mandibular nerve is essential for healthcare professionals in various fields. In this article, we will explore the intricate details of the mandibular nerve, including its pathway, exit and entry points, as well as its clinical relevance.

Understanding the Mandibular Nerve

Anatomy of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, a branch of the trigeminal ganglion, is a crucial component of the sensory innervation of the face. It originates from the trigeminal ganglion, a sensory ganglion located in the middle cranial fossa. This ganglion is responsible for relaying sensory information from the face to the brain.

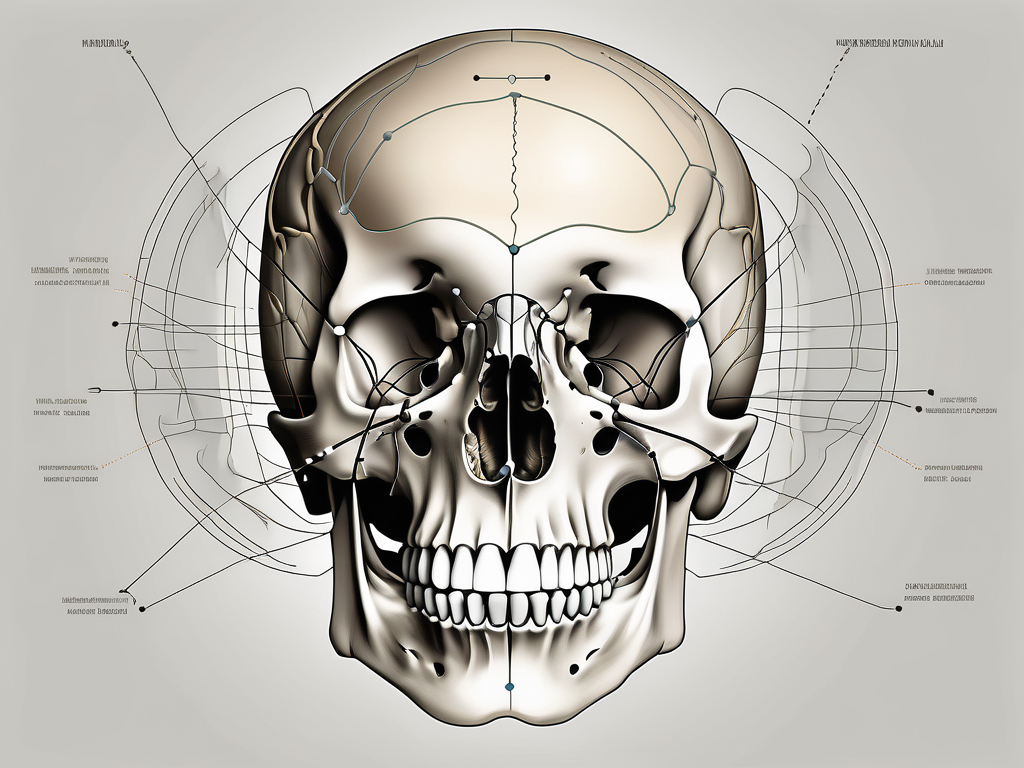

Emerging from the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus, the mandibular nerve embarks on a fascinating journey through the intricate network of the skull. It passes through the foramen ovale, a small opening in the skull, which allows it to exit the cranial cavity and enter the infratemporal fossa.

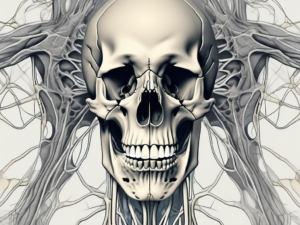

Once it emerges from the skull, the mandibular nerve assumes a key role in supplying innervation to the lower face. It branches out into multiple smaller nerves, each with its own specific function and territory of sensory innervation.

One of these branches is the auriculotemporal nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the external ear and the skin of the temple. Another branch is the inferior alveolar nerve, which supplies sensory innervation to the lower teeth and gums. Lastly, the lingual nerve, another branch of the mandibular nerve, provides sensory innervation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

Function of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve plays a vital role in both sensory and motor functions. As a sensory nerve, it carries information from the lower face, including pain, touch, and temperature sensations. These sensations are transmitted to the trigeminal nucleus within the brainstem, where they are further processed and relayed to higher centers for appropriate perception and response to stimuli.

In addition to its sensory role, the mandibular nerve also provides motor innervation to the muscles of mastication. These muscles, including the temporalis, masseter, and lateral and medial pterygoids, are responsible for the complex movements involved in chewing and grinding food. The mandibular nerve also innervates the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the mylohyoid muscle, which play crucial roles in jaw movement and swallowing.

Understanding the anatomy and function of the mandibular nerve is essential in various fields of medicine, including dentistry, neurology, and maxillofacial surgery. It allows healthcare professionals to diagnose and treat conditions affecting the sensory and motor functions of the lower face, ensuring optimal patient care and well-being.

The Pathway of the Mandibular Nerve

Origin of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, an important branch of the trigeminal nerve, originates from the trigeminal ganglion, which is situated within the cavernous sinus. The trigeminal ganglion, also known as the semilunar ganglion, contains the cell bodies of the sensory neurons that transmit signals from the face to the brain. These sensory neurons play a crucial role in our ability to feel and perceive sensations on the face.

From the trigeminal ganglion, the mandibular nerve emerges and takes a complex course to reach its destination. It is fascinating to note that the trigeminal ganglion is not the only structure involved in the origin of the mandibular nerve. It receives contributions from other ganglia as well, such as the otic ganglion and the submandibular ganglion. This intricate network of ganglia ensures the proper functioning of the mandibular nerve and its branches.

Course of the Mandibular Nerve

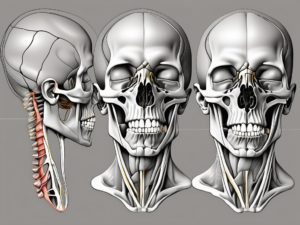

After exiting the skull through the foramen ovale, a small opening located in the sphenoid bone, the mandibular nerve embarks on an intriguing journey through the infratemporal fossa. This fossa, located on the side of the skull, is a complex anatomical region that houses various important structures, including muscles, blood vessels, and nerves.

Within the infratemporal fossa, the mandibular nerve gives rise to several branches that supply sensory innervation to various facial structures. One of these branches is the auriculotemporal nerve, which provides sensory innervation to the skin of the temple, external ear, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) region. This nerve plays a significant role in our ability to feel touch, temperature, and pain in these areas.

Another important branch of the mandibular nerve is the inferior alveolar nerve. This nerve descends into the mandibular canal, a bony tunnel within the mandible, and is responsible for transmitting sensory information from the lower teeth and gums. It allows us to perceive sensations such as pressure, temperature, and pain in our lower jaw, ensuring our ability to chew, bite, and speak effectively.

In addition to the auriculotemporal and inferior alveolar nerves, the mandibular nerve also gives rise to the lingual nerve. The lingual nerve provides innervation to the tongue mucosa, sides of the tongue, and the floor of the mouth. This nerve enables us to taste, feel texture, and perceive temperature in these areas, contributing to our overall sensory experience during eating and speaking.

The course of the mandibular nerve is not only anatomically fascinating but also clinically significant. Understanding its pathway and branches is crucial for dental and maxillofacial surgeons, as well as neurologists, in diagnosing and treating various conditions that may affect the sensory function of the face and jaw.

Exit and Entry Points of the Mandibular Nerve

Where the Mandibular Nerve Exits

The mandibular nerve exits the skull through the foramen ovale, a bony aperture located in the posterior part of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. This foramen serves as a channel through which the mandibular nerve and its branches pass, connecting the intracranial structures to the lower face.

As the mandibular nerve emerges from the foramen ovale, it embarks on a complex journey, branching out to provide sensory innervation to various regions of the face. One of its major branches, the inferior alveolar nerve, descends into the mandibular canal, running alongside the roots of the lower teeth. This branch is responsible for transmitting sensations from the lower teeth, gums, and lower lip.

Another branch of the mandibular nerve, known as the buccal nerve, travels anteriorly, passing through the buccinator muscle and supplying sensory information to the cheek and the skin overlying the buccal region.

Additionally, the auriculotemporal nerve, another significant branch of the mandibular nerve, courses upwards and backwards, wrapping around the middle meningeal artery before reaching the temporal region. This branch provides sensory innervation to the scalp, the side of the head, and the external ear.

Where the Mandibular Nerve Enters

While the mandibular nerve exits through the foramen ovale, it re-enters the oral cavity via the mandibular foramen. This tiny opening is situated on the medial surface of the mandible, near the posterior end of the mandibular body. Through the mandibular foramen, the mandibular nerve and its branches gain access to the lower jaw, teeth, and surrounding structures.

Upon entering the mandibular foramen, the mandibular nerve divides into its terminal branches, each responsible for supplying sensory innervation to specific regions of the lower face. One of these branches, the mental nerve, emerges from the mental foramen, located on the anterior surface of the mandible, and provides sensation to the chin and lower lip.

Another important branch, the lingual nerve, courses anteriorly along the floor of the mouth, supplying sensory information to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. This branch also gives off smaller branches that innervate the lingual gingiva, the floor of the mouth, and the lingual mucosa.

Furthermore, the mylohyoid nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve, descends into the mylohyoid groove on the medial surface of the mandible, innervating the mylohyoid muscle and the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. This nerve also provides sensory innervation to the skin overlying the chin and the floor of the mouth.

It is fascinating to consider the intricate network of nerves that traverse the exit and entry points of the mandibular nerve. These pathways ensure the transmission of sensory information from the lower face to the brain, allowing us to perceive and respond to various stimuli in our environment.

Clinical Significance of the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve, also known as the inferior alveolar nerve, is a branch of the trigeminal nerve and plays a crucial role in the sensory innervation of the lower face and oral cavity. It provides sensation to the lower teeth, gums, and chin, as well as the mucous membranes of the mouth.

Disorders Related to the Mandibular Nerve

The mandibular nerve can be affected by various pathological conditions, leading to sensory disturbances and functional impairment. One common disorder involving the mandibular nerve is trigeminal neuralgia, characterized by severe facial pain in the distribution of the sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve. This excruciating pain can be triggered by simple activities such as eating, talking, or even touching the face.

Other conditions, such as trigeminal neuropathy or trauma to the mandibular nerve, can also result in pain, numbness, or abnormal sensation in the lower face and oral cavity. Trigeminal neuropathy refers to damage or dysfunction of the trigeminal nerve, which can cause similar symptoms as trigeminal neuralgia. Trauma to the mandibular nerve can occur due to accidents, dental procedures, or surgical interventions in the vicinity of the nerve.

It is important to note that any symptoms involving the mandibular nerve should be evaluated by a healthcare professional. Self-diagnosis and self-medication may not lead to accurate results and could potentially worsen the condition. Consulting with a doctor or a specialist in neurology or oral and maxillofacial surgery is advised for a proper assessment and management plan.

Treatment Options for Mandibular Nerve Issues

The management of mandibular nerve-related disorders depends on the underlying cause and the severity of symptoms. In many cases, conservative measures such as pain medications and physical therapy may provide relief. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and anticonvulsant medications are commonly prescribed to alleviate pain and reduce nerve sensitivity.

However, in more severe cases or when conservative options fail, surgical interventions may be considered. Microvascular decompression is a surgical procedure that involves relieving pressure on the nerve by repositioning blood vessels that may be compressing it. This procedure has shown promising results in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.

Another surgical option is radiofrequency ablation, which uses heat to selectively destroy nerve fibers and interrupt pain signals. This procedure is often performed under local anesthesia and can provide long-lasting pain relief.

The choice of treatment should be tailored to the individual patient in collaboration with their healthcare provider. Factors such as the patient’s overall health, the severity of symptoms, and the potential risks and benefits of each treatment option should be taken into consideration.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Mandibular Nerve

Common Misconceptions about the Mandibular Nerve

One common misconception is that only dental pain is associated with the mandibular nerve. While it is true that the inferior alveolar nerve provides sensory innervation to the lower teeth and gums, the mandibular nerve has a much broader role. It supplies sensation to the entire lower face, including the skin, mucous membranes, and other oral structures.

It is important to note that the mandibular nerve is not solely responsible for dental pain. While dental issues can certainly cause discomfort, there are various other factors that can contribute to pain in the lower face. For example, trauma or inflammation in the surrounding tissues can also lead to discomfort and affect the function of the mandibular nerve.

Another misconception is that mandibular nerve-related disorders are solely dental in nature. However, conditions like trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuropathy can affect individuals regardless of their dental health status. These disorders are neurological in nature and require specialized evaluation and management.

Trigeminal neuralgia is a condition characterized by severe facial pain, often triggered by simple activities such as eating or speaking. It is caused by irritation or damage to the trigeminal nerve, which includes the mandibular nerve. Trigeminal neuropathy, on the other hand, refers to a dysfunction of the trigeminal nerve, leading to abnormal sensations, numbness, or pain in the face.

It is crucial to recognize that mandibular nerve-related disorders can have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life. The pain and discomfort associated with these conditions can be debilitating, affecting daily activities and overall well-being. Seeking proper medical attention and exploring appropriate treatment options is essential for managing these disorders effectively.

Recent Advances in Mandibular Nerve Research

Ongoing research continues to shed light on various aspects of the mandibular nerve. Scientists are exploring new treatment modalities and surgical techniques to improve outcomes for patients with mandibular nerve-related disorders. Recent studies have also focused on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying nerve development and regeneration, aiming to develop potential therapeutic targets for nerve-related pathologies.

One area of research that shows promise is the use of nerve growth factors to promote nerve regeneration and repair. These growth factors can stimulate the growth of new nerve fibers and enhance the recovery process in cases of nerve damage or injury. Additionally, researchers are investigating the potential of stem cell therapy in restoring the function of damaged mandibular nerves, offering hope for individuals suffering from nerve-related disorders.

Understanding the intricate mechanisms of nerve development and regeneration is crucial for advancing treatment options and improving patient outcomes. By unraveling the complex molecular pathways involved in nerve repair, researchers aim to develop targeted therapies that can restore normal function and alleviate the symptoms associated with mandibular nerve-related disorders.

In conclusion, the mandibular nerve plays a critical role in the sensory innervation of the lower face. Understanding its anatomy, function, and clinical significance is essential for healthcare professionals and individuals seeking knowledge about the intricacies of facial sensation. If you have any concerns or symptoms related to the mandibular nerve, it is advised to consult with a healthcare professional experienced in neurology or oral and maxillofacial surgery. Together, they can provide proper evaluation, guidance, and management tailored to your specific needs.